Date:2018-05-30 16:34:37 Views:710 Source:

Source: Lehigh University

Left to right: Research contributors and Lehigh electrical and computer engineering graduate students Ji Chen, Liang Gao and Yuan Jin stand in the Terahertz Photonics laboratory of Sushil Kumar in the Sinclair Building at Lehigh University. Credit: Sushil Kumar, Lehigh University

The ability to harness light into an intense beam of monochromatic radiation in a laser has revolutionized the way we live and work for more than fifty years. Among its many applications are ultrafast and high-capacity data communications, manufacturing, surgery, barcode scanners, printers, self-driving technology and spectacular laser light displays. Lasers also find a home in atomic and molecular spectroscopy used in various branches of science as well as for the detection and analysis of a wide range of chemicals and biomolecules.

Lasers can be categorized based on their emission wavelength within the electromagnetic spectrum, of which visible light lasers—such as those in laser pointers—are only one small part. Infrared lasers are used for optical communications through fibers. Ultraviolet lasers are used for eye surgery. And then there are terahertz lasers, which are the subject of investigation at the research group of Sushil Kumar, an associate professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Lehigh University.

Terahertz lasers emit radiation that sits between microwaves and infrared light along the electromagnetic spectrum. Their radiation can penetrate common packaging materials such as plastics, fabrics and cardboard, and are also remarkably effective in optical sensing and analysis of a wide variety of chemicals. These lasers have the potential for use in non-destructive screening and detection of packaged explosives and illicit drugs, evaluation of pharmaceutical compounds, screening for skin cancer and even the study of star and galaxy formation.

Applications such as optical spectroscopy require the laser to emit radiation at a precise wavelength, which is most commonly achieved by implementing a technique known as "distributed-feedback." Such devices are called single-mode lasers. Requiring single-mode operation is especially important for terahertz lasers, since their most important applications will be in terahertz spectroscopy. Terahertz lasers are still in a developmental phase and researchers around the world are trying to improve their performance characteristics to meet the conditions that would make them commercially viable.

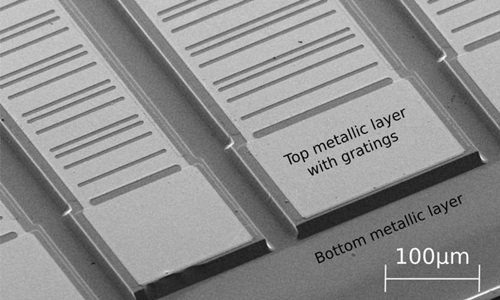

Top: A scanning electron microscope image of a high-power surface-emitting terahertz semiconductor laser with hybrid gratings. Multiple lasers are fabricated on a Gallium Arsenide semiconductor chip. Each laser is approximately 1.5mm long, 10 microns thick and varies in width between 0.1mm to 0.2mm. Bottom: Artistic illustration of the terahertz laser in operation. The laser's semiconductor material is sandwiched between metallic layers on both top and bottom. A periodic grating is introduced in the top metallic layer in the form of apertures from where light could leak out. An interplay of second- and fourth-order Bragg gratings (manifested as alternating single and double slits) leads to intense radiation from alternating periods of the periodic structure, combining coherently into a high quality single-lobed laser beam in the surface-normal direction. Credit: Sushil Kumar, Lehigh University

As it propagates, terahertz radiation is absorbed by atmospheric humidity. Therefore, a key requirement for such lasers is an intense beam such that it could be used for optical sensing and analysis of substances kept at a standoff distance of several meters or more, and not be absorbed. To this end, Kumar's research team is focused on improving their intensity and brightness, achievable in part by increasing optical power output.

In a recent paper published in the journal Nature Communications, the Lehigh team—supervised by Kumar in collaboration with Sandia National Laboratories—reported on a simple yet effective technique to enhance the power output of single-mode lasers that are "surface-emitting" (as opposed to those using an "edge-emitting" configuration). Of the two types, the surface-emitting configuration for semiconductor lasers offers distinctive advantages in how the lasers could be miniaturized, packaged and tested for commercial production.

The published research describes a new technique by which a specific type of periodicity is introduced in the laser's optical cavity, allowing it to fundamentally radiate a good quality beam with increased radiation efficiency, thus making the laser more powerful. The authors call their scheme as having a "hybrid second- and fourth-order Bragg grating" (as opposed to a second-order Bragg grating for the typical surface-emitting laser, variations of which have been used in a wide variety of lasers for close to three decades). The authors claim that their hybrid grating scheme is not limited to terahertz lasers and could potentially improve performance of a broad class of surface-emitting semiconductor lasers that emit at different wavelengths.

The report discusses experimental

results for a monolithic single-mode terahertz laser with a power output of 170

milliwatts, which is the most powerful to date for such class of lasers. The

research shows conclusively that the so-called hybrid grating is able to make

the laser emit at a specific desired wavelength through a simple alteration in

the periodicity of imprinted grating in the laser's cavity while maintaining its

beam quality. Kumar maintains that power levels of one watt and above should be

achievable with future modifications of their technique—which might just be the

threshold needed to be overcome for industry to take notice and step into

potential commercialization of terahertz laser-based instruments.